Black students are more likely to be suspended from U.S. public schools — even as tiny preschoolers.

The racial disparities in American education, from access to high-level classes and experienced teachers to discipline, were highlighted in a report released Friday by the Education Department's civil rights arm.

The suspensions — and disparities — begin at the earliest grades.

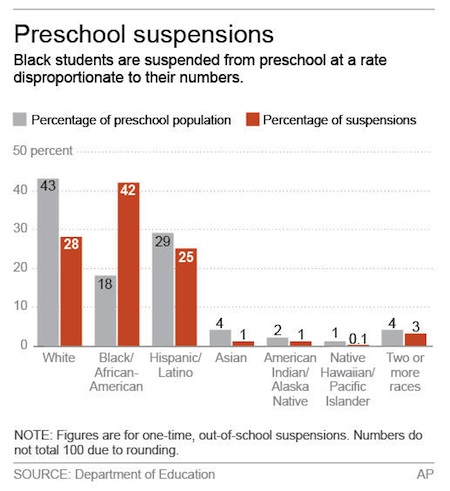

Black children represent about 18 percent of children in preschool programs in schools, but they make up almost half of the preschoolers suspended more than once, the report said. Six percent of the nation's districts with preschools reported suspending at least one preschool child.

Advocates long have said get-tough suspension and arrest policies in schools have contributed to a "school-to-prison" pipeline that snags minority students, but much of the emphasis has been on middle school and high school policies. This was the first time the department reported data on preschool discipline.

Earlier this year, the Obama administration issued guidance encouraging schools to abandon what it described as overly zealous discipline policies that send students to court instead of the principal's office. But even before the announcement, school districts have been adjusting policies that disproportionately affect minority students.

Overall, the data show that black students of all ages are suspended and expelled at a rate that's three times higher than that of white children. Even as boys receive more than two-thirds of suspensions, black girls are suspended at higher rates than girls of any other race or most boys.

The data doesn't explain why the disparities exist or why the students were suspended.

"It is clear that the United States has a great distance to go to meet our goal of providing opportunities for every student to succeed," Education Secretary Arne Duncan said in a statement.

"This critical report shows that racial disparities in school discipline policies are not only well documented among older students, but actually begin during preschool," Attorney General Eric Holder said. "Every data point represents a life impacted and a future potentially diverted or derailed. This administration is moving aggressively to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline in order to ensure that all of our young people have equal educational opportunities."

Nationally, 1 million children were served in public preschool programs, with about 60 percent of districts offering preschool during the 2011-2012 school year, according to the data. The data show nearly 5,000 preschoolers were suspended once. At least 2,500 were suspended more than once.

Hispanic children made up nearly one-third of all preschoolers, but they made up 25 percent of the preschoolers suspended once and 20 percent of preschoolers suspended more than once.

Reggie Felton, interim associate executive director at the National School Boards Association, called the rates "unacceptable." He said there's more training going on to ensure teachers are aware of the importance of keeping students in school.

Daniel Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies for the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, said the findings are disturbing because the suspended preschoolers are unlikely to be presenting a danger, such as a teenager bringing a gun to school.

"Almost none of these kids are kids that wouldn't be better off with some support from educators," Losen said. "Just kicking them out of school is denying them access to educational opportunity at such a young age. Then, as they come in for kindergarten, they are just that much less prepared."

Losen said it's appropriate to discipline a 4-year-old, but a more appropriate response might be moving them to a different educational setting with additional services.

"Most preschool kids want to be in school," Losen said. "Kids just don't understand why they can't go to school."

Kimbrelle Lewis, principal of Raleigh-Bartlett Meadows Elementary School in Memphis, said she's never suspended a child in her school's preschool program and would only consider it in an "extreme circumstance." She said her district provides behavior specialists and other services to children with discipline problems so strategies can be worked out with teachers and parents if preschoolers need additional support.

If there are racial disparities among preschoolers disciplined, "I do think it's something to look at. I think it's a conversation to have," said Lewis, who served on a committee with the National Association of Elementary School Principals looking at issues affecting younger school children.

Dennis Van Roekel, the president of the National Education Association teachers' union, said in a statement that the findings show that "too many children don't have equitable access to experienced and fully licensed teachers."

"The inequities detailed in this report have been caused, at least in part, by policies that disregard the professionalism of teaching and create a revolving door of under-prepared and under-supported novices who leave before they've reached the levels of mastery required to truly make a difference," Van Roekel said.

Judith Browne Dianis, co-director of the Advancement Project, a think tank that specializes in social issues affecting minority communities, said the findings didn't surprise her.

"I think most people would be shocked that those numbers would be true in preschool, because we think of 4- and 5-year-olds as being innocent," she said. "But we do know that schools are using zero tolerance policies for our youngest also, that while we think our children need a head start, schools are kicking them out instead."