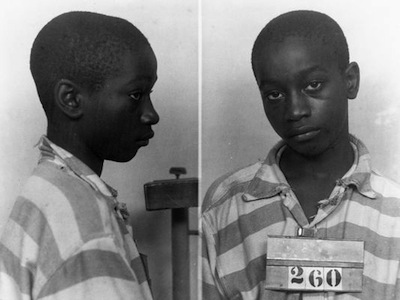

Supporters of a 14-year-old black boy executed in 1944 for killing two white girls are asking a South Carolina judge to take the unheard-of move of granting him a new trial in hopes he will be cleared of the charges.

George Stinney was convicted on a shaky confession in a segregated society that wanted revenge for the beating deaths of two girls, ages 11 and 7, according to the lawsuit filed last month on Stinney's behalf in Clarendon County.

The request for a new trial has an uphill climb. The judge may refuse to hear it at all, since the punishment was already carried out. Also, South Carolina has strict rules for introducing new evidence after a trial is complete, requiring the information to have been impossible to discover before the trial and likely to change the results, said Kenneth Gaines, a professor at the University of South Carolina's law school.

"I think it's a longshot, but I admire the lawyer for trying it," Gaines said, adding that he's not aware of any other executed inmates in the state being granted a new trial posthumously.

The request for a new trial is largely symbolic, but Stinney's supporters say they would prefer exoneration to a pardon.

Stinney's case intersects some long-running disputes in the American legal system — the death penalty and race. At 14, he's the youngest person executed in the United States in past 100 years. He was electrocuted just 84 days after the girls were killed in March 1944.

The request for a new trial includes sworn statements from two of Stinney's siblings who say he was with them the entire day the girls were killed. Notes from Stinney's confession and most other information deputies and prosecutors used to convict Stinney in a one-day trial have disappeared along with any transcript of the proceedings. Only a few pages of cryptic, hand-written notes remain, according to the motion.

"Why was George Stinney electrocuted? The state can't produce any paperwork to justify why he was," said George Frierson, a local school board member who grew up in Stinney's hometown hearing stories about the case, and decided six years ago to start studying it and pushing for exoneration.

The South Carolina Attorney General's Office will likely argue the other side of the case before the Clarendon County judge. A spokesman said their lawyers had not seen the motion and do not comment on pending cases. A date for a hearing on the matter has not been set.

The girls were last seen looking for wildflowers in the tiny, racially-divided mill town of Alcolu about 50 miles southeast of Columbia. Stinney's sister, who was 7 at the time, said in her new affidavit that she and her brother were letting their cow graze when the girls asked them where they could find flowers called maypops. The sister, Amie Ruffner, said her brother told them he didn't know and the girls left.

"It was strange to see them in our area, because white people stayed on their side of Alcolu and we knew our place," Ruffner wrote.

The girls never came home, and hundreds of people searched for them through the night. They were found the next morning in a water-filled ditch, their heads beaten with a hard object, likely a railroad spike.

Deputies got a tip the girls had been seen talking to Stinney. They came to Stinney's home and took him away. His family wouldn't see the boy again until after his trial. Newspaper accounts suggested a lynch mob was nearly formed to attack the teen in jail.

Stinney's dad worked for the major mill in town and lived in a company house. He was ordered to leave after his son was arrested, said Stinney's brother Charles Stinney, who was 12 when his older brother was arrested. Charles Stinney's statement explains why the family didn't speak to authorities at the time.

"George's conviction and execution was something my family believed could happen to any of us in the family. Therefore, we made a decision for the safety of the family to leave it be," Charles Stinney wrote in his sworn statement.

Charles Stinney said he remembered the events vividly because "for my family, Friday, March 24, 1944, and the events that followed were our personal 9/11."

Both statements were made in 2009. Lawyer Steve McKenzie said he planned to file the request for a new trial then, but heard from a man in Tennessee who claimed his grandfather was with George Stinney the day of the killings. McKenzie thought the information from someone not related to Stinney would be especially powerful, but the person suddenly stopped cooperating after stringing the lawyers along for years.

The request for a new trial points out that at 95 pounds, Stinney likely couldn't have killed the girls and dragged them to the ditch.

The motion also hints at community rumors of a deathbed confession from a white man several years ago and the possibility Stinney either confessed because his family was threatened or he was given ice cream. But the court papers provide little information, and the lawyers also wouldn't elaborate.

At 14, Stinney was the youngest person executed in this country in the past 100 years, according to statistics gathered by the Death Penalty Information Center.

Newspaper stories from his execution had witnesses saying the straps to keep him in the electric chair didn't fit around his small frame, and an electrode was too big for his leg.

Executing teens wasn't uncommon at that time. Florida put a 16-year-old boy to death for rape in 1944, and Mississippi, Nevada, Ohio and Texas executed 17-year-olds that year.

Lawyers also filed a request for to pardon Stinney before the state Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services in case the new trial is not granted.

There is precedent for that. In 2009, two great-uncles of syndicated radio host Tom Joyner were pardoned by the board nearly 100 years after they were sent to the electric chair for the death of a Confederate Army veteran. Joyner's lawyers showed evidence the men were framed by a small-time criminal who took a plea deal that saved his life and testified against them.

But Frierson said a pardon would be little comfort to him in the Stinney case. "The first step in a pardon is to admit you are wrong and ask for forgiveness," Frierson said. "This boy did nothing wrong."