This past April, the Youth Against Settlements website posted a letter from Samer Tariq Issawi, a Palestinian imprisoned by the Israeli government. “I invite you to visit me, to see a skeleton tied to his hospital bed, and around him three exhausted jailers,” he wrote. “Sometimes they have their appetizing food and drinks around me. The jailers watch my suffering, my loss of weight and my gradual melting.”

Initially locked up in 2002 for violent crimes, Issawi was released in 2011 as part of the Gilad Shalit prisoner exchange. In July 2012, Israeli forces imprisoned him again after he violated the terms of his parole by traveling to the West Bank. A military committee refused to let him see the evidence against him as it sought to impose the remainder of his original twenty-six-year sentence. Facing an unfair trial and seventeen more years in prison, he started a hunger strike in August 2012. He was still fasting on April 22 when the committee held a bedside hearing. Issawi had become a hero to many Palestinians, a symbol of resistance. News of his debilitation had triggered clashes between Israeli soldiers and Palestinian protesters in Bethlehem. Clearly fearing what would happen if he died, the committee agreed to release him in eight months. If Israel keeps its word, Issawi will leave prison in December.

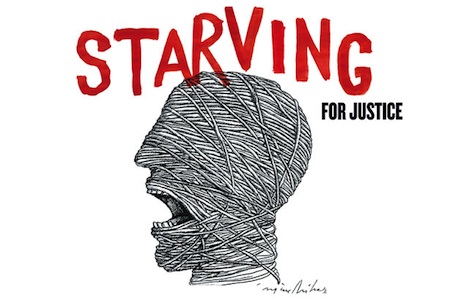

This was the year of the hunger strike—did you notice? The mainstream press didn’t. While the fasts in Guantánamo and California received significant coverage, the broader phenomenon went unremarked. There were dozens, perhaps hundreds, of sustained hunger strikes all over the world. In fact, it’s difficult to identify sizable countries where there wasn’t at least one noteworthy fast. Most took place in prisons. Together, the strikes reflect the universal disregard for the rights of prisoners as well as the worldwide increase in radical protest of all forms.

The hunger strike dates back thousands of years in countries as different as India and Ireland, but it became more common in the early twentieth century, as the advent of mass communications enabled fasters and their supporters to generate much greater publicity. A hunger strike is usually an act of desperation, but it is also a rational response to state oppression. Fasters have included activists no less esteemed than Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Cesar Chavez, the suffragists and the students at Tiananmen Square.

Activists fasted this year for the same reason this ancient tactic has endured: it’s effective, all the more so when the possibility of martyrdom exists. “No target of protest wants that on their hands,” says Stephen Scanlan, a sociologist at Ohio University who has researched hunger strikes. “Once a protest campaign reaches this level, concessions are typically won.”

Yet serious hunger strikers risk illness and sometimes death. Many also suffer abuse. First-person accounts from Guantánamo reveal the violence of force-feeding prisoners, which violates international law, yet governments do it with impunity. This past July, in response to high-profile hunger strikes by Palestinian prisoners, Israel’s Justice Ministry began drafting a bill that would allow force-feeding. As governments grow ever more determined to deny martyrdom to hunger strikers, force-feeding is becoming an urgent civil liberties issue, one that ought to unite prisoners’ rights, anti-torture and right-to-die advocates.

In 2013, hunger strikers seemed to be everywhere. People of all regions, races and religious groups fasted, targeting governments of all kinds. That said, there were trends.

Prisoners have made up the majority of hunger strikers in the modern era, and this year was no exception. From Colombia to Russia to Vietnam, they fasted to protest abuse, unjust imprisonment and inhumane conditions. The fast is a logical form of protest in a place that breeds desperation and robs people of their autonomy. To refuse to eat is one of the few ways prisoners can exercise control, and usually the only way they can pressure the state.

Of the fasts outside prisons, many took place in refugee detention centers. It must be a special kind of hell, the bottom beneath the bottom, to escape persecution, war or a natural disaster only to be locked up indefinitely in a place every bit as dehumanizing as a prison. At the Menogia detention center in Cyprus, twenty-five Syrian refugees fasted to try to end their mistreatment, which included the denial of food and medical care. Enduring horrid conditions at the Békéscsaba detention camp in Hungary, five Malian refugees stopped eating, inspiring fifty-five other refugees to join them.

Hunger strikes were also notably common in Middle Eastern countries, including ones untouched by war or revolution: Oman, Qatar, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In Yemen, twenty-two men jailed without charge tried to compel prison officials to comply with a cabinet decision ordering the release of nineteen of them. In September, Iraqi forces killed fifty-two Iranian exiles and took seven into custody, purportedly to quell unrest. The attack triggered a mass fast at Camp Liberty, the former US military base that now houses 3,000 Iranian exiles.

The hunger-strike watchers I spoke with agreed that the tactic is being used more frequently. They cautioned, however, that a lack of comparative data makes it difficult to distinguish fact from perception. But perception influences fact: social media increase public awareness of hunger strikes, which in turn increases their prevalence. “There is a feedback loop in which social media creates a greater audience for those strikes and more hope for success—if only for the success of some public attention,” says Sharman Apt Russell, author of Hunger: An Unnatural History.

A study points to another explanation for the increase. “Starving for Change: The Hunger Strike and Nonviolent Action, 1906–2004,” by Scanlan, Laurie Cooper Stoll and Kimberly Lumm, finds that hunger strikes spike during eras of protest. Today’s fasts, then, can be understood as part of the activism that has erupted across the globe—from uprisings in the Middle East, anti-austerity protests in Europe and resistance in Russia to deepening corruption and repression, the Occupy movement, national security whistleblowing in the United States, and on and on.

But no one should glamorize the tactic. The fasting body usually begins to fall apart after about forty days. In Hunger: An Unnatural History, Russell describes what happens:

First you have double vision. Then your sight dims. You vomit green bile. Your speech is slurred. You can’t hear very well. You have jaundice. You have scurvy from lack of Vitamin C. Your gums begin to bleed. You may be bleeding into your stomach and intestines. You may have thiamine deficiency, which weakens the muscles of the heart and causes lesions in the central and peripheral nervous system. As your nerve fibers degenerate, you feel a sharp pain down your arms. One day, you cannot move your legs. Niacin deficiency may be the reason for the sores in your mouth. You have what is called “skin breakdown.” This is the process of starving to death.

This grisly prospect accounts for its power. The “stunt” becomes, at a certain point, proof of its own seriousness. It says, “I am willing to die for this,” or, “I would rather die than live like this.” It exposes the brutality of state power and calls the bluff of government leaders who claim, as all government leaders do, to oppose suffering. In 1981, Bobby Sands led a fast of Irish Republican Army prisoners and died from starvation along with nine others. Their deaths turned Irish Republicanism into an international cause and Sinn Féin into a political power.

Impending martyrdom explains why the displays of support for anarchist Kostas Sakkas unsettled the Greek government. He was arrested in December 2010 for alleged membership in the Conspiracy of Fire Nuclei, which the government considers a terrorist organization. Imprisoned for two and a half years without a trial, he stopped eating in June. “I would like to clarify that, for me, the choice to go on hunger strike is not a gesture of despair, but a choice to continue the fight,” he wrote. Amid widespread austerity-induced agitation on both the left and right, 6,000 Sakkas supporters marched through Athens on June 29. The left-wing opposition party Syriza called for his release and urged the European Court of Human Rights to intervene. More than a month into his fast, Sakkas appeared at the barred window of his hospital room and addressed protesters. “To victory! Until the end!” he shouted. The anarchist activist and alleged terrorist was becoming a folk hero. On July 12, two days after a doctor reported that Sakkas was in the “final stage” of life, the government agreed to release him on bail.

Such victories, narrow but significant, were not uncommon this year. In June, Yemen released seventeen of the twenty-two hunger-striking prisoners. In response to a July fast by dozens of prisoners—including some who had sewed their mouths shut—at Colombia’s Doña Juana Penitentiary, the bureau of prisons agreed to improve medical care and to investigate three deaths caused by a lack of it. In Russia, Maria Alyokhina, one of three Pussy Riot members imprisoned for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred,” stopped fasting when officials at her prison in the Ural Mountains ended the security crackdown pegged to her parole hearing, which, she said, had turned fellow prisoners against her. Her bandmate, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, also used a hunger strike to pressure the government. From Penal Colony No. 14 in Mordovia, Tolokonnikova wrote a letter in September detailing the reasons for her fast: seventeen-hour workdays, filth, sadistic prison guards, collective punishment. “I demand that we be treated like human beings, not slaves,” she wrote, reigniting debate in Russia about prison conditions. The government acceded to one of her demands by transferring her, but the move was likely an effort to silence her because her new prison is in Siberia. In August, four months after the Israeli government conceded to Issawi, it agreed to take hunger striker Dirar Abu Sisi out of solitary confinement. These victories follow a wider one in 2012, when a fast by 1,500 Palestinian prisoners secured family visits for 400 and the release of nineteen from solitary confinement.

Solitary confinement drove the hunger strike in California prisons, which some 30,000 people joined at the outset. Their number quickly dwindled, but forty days in, dozens were still fasting. In 2011, after the previous major fast in California’s prisons, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan Méndez said solitary confinement longer than fifteen days should be banned. Nearly 200 prisoners have spent more than a decade in solitary in California. In July, hunger striker Michael Russell wrote a piece that poetically conveyed its horror: “I’ve spent a quarter of my life in this prison’s cages, in its mud, learning to deal with the loud rhythm, the madness and isolation, the absence from my family and friends that has turned me into a total stranger, with so much empty uncertainty. I don’t sit here and cry. Nobody does.”

Unlike Israel’s Palestinian prisoners, California’s are not part of a larger political movement, at least not one with the capacity to frighten the government. Even after hunger striker Billy Michael Sell hanged himself, Governor Jerry Brown refused to negotiate. Officials claimed that gangs were behind the fast and, absurdly, that solitary confinement didn’t even exist in California. Prisoners called off the fast in early September after two state legislators vowed to hold a hearing on solitary confinement—hardly a major victory.

Yet solitary confinement has become a more prominent issue, and California’s prisoners deserve much of the credit. While a PR victory is not their goal, it’s a prerequisite for a substantive victory. Solitary confinement—“even more damaging than physical torture,” writes Atul Gawande—will someday be widely seen as barbaric and banned.

Guantánamo’s hunger strikers also won that insufficient prize, attention. What began as “just another” fast at Gitmo became a major story as more than 100 prisoners joined. Unable to project images to the world, fasters like Shaker Aamer relied on words published with the help of their lawyers. Aamer is a Saudi resident of Britain imprisoned for nearly twelve years without charge even though the US government has twice cleared him for release. “I do sometimes worry that I am going to die in here,” he wrote in the Daily Mail. “I hope I don’t, but if the worst comes to the worst, I want my kids to know that I stood up for a principle.”

Guantánamo’s hunger strikers managed to do what civil liberties and human rights groups had been unable to do: force President Obama to take up an issue he had ignored for months. Its subsequent redisappearance from the DC discussion underscores, rather than diminishes, their accomplishment. And their accomplishment wasn’t wholly intangible. The hunger strikers got Obama to release two men to Algeria in August—the first such transfers in nearly a year.

Of course, it wasn’t only the fast that commanded attention; it was also the government’s response to the fast. Because mass death would be even worse PR than mass abuse, the Obama administration has waged a brutal and illegal campaign of force-feeding. I use the present tense because Gitmo prisoners are still being “food-boarded,” as Jon Stewart calls it. More recently, in August, a federal district judge granted California authority to force-feed prisoners. It was preparing to do so when the strike ended. The horror of force-feeding is all the more reason not to root for hunger strikes to happen even as we on the left root for them to succeed.

It’s likely that as this age of protest carries on, so too will hunger strikes. We should spotlight this trend and, more important, the causes of hunger strikes. In the summer, Edward Snowden’s search for asylum prompted American pundits to denounce the human rights records of other countries, which, they claimed, were far inferior to that of the United States. The discussion obscured an important truth: that all governments—democracies and dictatorships and combinations thereof—violate the rights and deny the dignity of the most marginalized people, especially those forced to live in cages. That’s why they starve themselves.