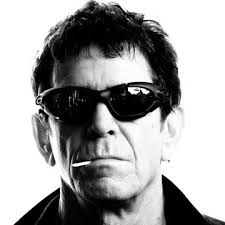

He'd already curtly dismissed a publicist who had dreamed for years of meeting his musical hero. Now Reed seemed to be debating whether my admitted sin — I wasn't a native New Yorker — was worth overlooking to get some business done.

Yes, Reed, who died Sunday at age 71 of liver disease related to a recent transplant, wasn't an easy man. New York isn't an easy town. Few artists reflected a city better than he did, and he found it an endless source of inspiration. The 2003 retrospective package we talked about claimed that status as a title: "NYC Man."

As a member of the Velvet Underground and later as a solo artist, Reed chronicled the rough side of a city at a time when it wasn't so hidden from view. Transvestites, drug addicts and prostitutes found a place in his music. Behind a loping bass line, the cinematic lyrics of "Walk on the Wild Side" brought that world to others. For many musicians, their best-known songs aren't necessarily representative of their work. That wasn't the case with Reed.

Many of his most popular songs, like "Sweet Jane," ''Rock and Roll" and "Heroin," dated from the period of the late 1960s into the 1970s with the Velvets and soon after they broke up.

The frequently challenging subject matter didn't lend itself to mass success and, "Walk on the Wild Side" excepted, Reed didn't achieve it. His singing voice didn't help, either; Reed had limited range and sang in a conversational style.

The Velvet Underground didn't sniff the top of the charts when alive, giving rise to a famous quote from producer and Roxy Music founder Brian Eno, who suggested that every one of the few people who bought their records, himself included, later started bands.

Many paid off their debts in tribute. U2 covered Reed's "Satellite of Love," the Cowboy Junkies did "Sweet Jane" and R.E.M. frequently performed "Pale Blue Eyes." His song "Perfect Day" had an extensive life, too.

Reed was an avant-garde artist who wore the black leather of a rocker and played a cutting guitar. Reed and his wife, performance artist Laurie Anderson, were a First Couple of an artistic scene that thrived on taking risks. Sometimes the risks didn't work — his last big project, the 2011 collaboration with Metallica called "Lulu," was widely seen as a clamorous mess — but very few people succeed at everything.

He was dismissive in our interview when asked what he hoped people would say about his work when he was gone.

"I don't give a (expletive)," he said. "Who knows or cares?

"I don't expect anything at all from anything and I never have," he said. "I'm not trying to change anybody's mind about anything. I'm not trying to win anybody over. I'm happy to get up in the morning. I can tie my shoelaces. I haven't got hit by a car. I just love the music and sound and wanted to make it better, so if someone else wanted to hear it, they'd get some bang for the buck."

The people who cared about his music always knew there was a heart beating strong beneath that gruff exterior. The wild side was hard to miss, but the tenderness of a "Pale Blue Eyes" is hard to forget, the regretful young man singing that he "thought of you as everything I've had but couldn't keep."

Reed's 1989 album, "New York," was a rocking, superbly written chronicle of a city in the midst of a crack epidemic, before it was later cleaned up.

On his song, "Dirty Blvd.," Reed details a scene of hustlers and hopelessness and those hookers again, zeroing in on Pedro, who escapes into his own dreams of transcending his environment with the help of a book of magic plucked from a garbage can.

Throughout the depressing scene he paints, Reed's voice is a monotone dripping in cynicism — until he gets to Pedro, where it lifts up a few notes, as if he can lift Pedro above the world he's living in to a better place. It's a moment of exquisite beauty.

Fly, fly away, Pedro.

You, too, Lou.